by Kevin Molloy

It was reaffirmed in the Hakluyt Society’s 2020 annual report that its main objective remains the research and editing of international travel records to educate, and make rare travel narratives accessible to, the ‘public’.[1] I say reaffirmed because this objective has guided the Society since 1847. Analysing how editors of the Society’s Main Series have achieved this objective reveals what the Society’s capacity to innovate its practices is.[2] In this blog I will analyse published accounts of travel in Africa to show how the Society has been innovative in developing its research practices and academic focuses, though in a mostly incremental way. The Society’s readership has typically gained access to knowledge about Africa through European accounts, whilst African experiences and expertise has not tended to be made accessible to the Society’s reading ‘public’. Based on my findings and its implications, I end by proposing a number of steps the Society could take to advance a decolonising agenda.

My analysis is based on a survey of published accounts related to Africa in the Society’s Main Series, which I conducted as part of an undergraduate research project at the University of Warwick. The blog consists of three parts. Section one highlights the Society’s dynamic innovations. The diversification of editors, such as the incorporation of female authors from 1909, reflects the Society’s willingness to develop its practices to achieve the publication of rare, educational, and accessible travel literature. Similarly, the adaptation of travel accounts, or the research, publication, and translation of authors of different geographical and ethnic origin, shows the Society’s commitment to presenting its ‘public’ with new histories. When examining African authors specifically, this practice dates to the publication of Leo Africanus’s History and Description of Africa (1895).[3] Section two is concerned with the Society’s more incremental innovations, specifically in relation to ‘travels of Africa’. I use the term ‘travels of Africa’ to denote a Main Series volume which lists a destination in Africa in its title, contents, or in the volume’s description on the Society’s online bibliography.[4] Further, I use the term ‘incremental’ to describe the gradual but modest changes in the publication of ‘travels of Africa’, as Eurocentric accounts continue to predominate the Society’s publications related to travel in Africa. Section three outlines potential steps to contribute to a decolonising agenda.[5] For instance, decolonisation could manifest as the incorporation of European and African accounts together in future ‘travels of Africa’ publications. Furthermore, decolonisation can be the promotion of African academics to be international representatives of the Society. By adopting these steps, the Society can strengthen African voices amongst its corpus, and amongst its academic body.

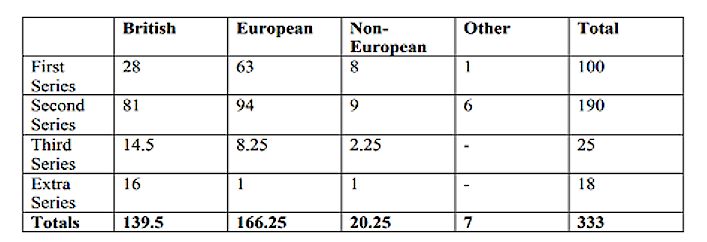

Over 175 years the Society has proven itself to be adaptable and innovative in its pursuit of publishing accessible, rare, and educational travel literature. Dorothy Middleton’s early history of the Society (1847-1923) recognised this by emphasising the Society’s inclusion of women, such as Dame Bertha Philpott, as Main Series volume editors.[6] More recently, Roy Bridges emphasised the Society’s publication of non-British travel narratives. The Society had published 166 editions of European travel by 2014.[7] The tradition of publishing European, rather than just British, accounts dates back to the Society’s founder, William Desborough Cooley, an armchair geographer who recognised the value of non-British sources at a time when overseas records were viewed sceptically by British academics.[8] Bridges also noted the Society’s continued adaptation of non-European records.[9] The publication of Jacob Wainwright’s travel, a Black African who recorded the journey of David Livingstone’s body from central Africa to Zanzibar, is one recent example. Yet, while the Society has proven itself to be innovative in these areas, it has only incrementally changed its practices in others.

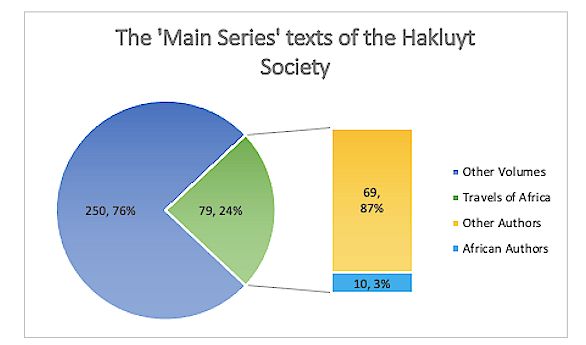

Seventy-nine Main Series volumes list a destination in Africa in its title, contents, or in the volume’s description, meaning that twenty-four per cent of the Hakluyt Society’s publications fit within my category of ‘travels of Africa’. Whilst this statistic illustrates the Society’s commitment to publishing international travel accounts, eighty-seven per cent of the ‘travels of Africa’ were adapted from European accounts.[10] Just five African authors have been published in the Main Series. These findings suggest that the Society’s public have historically learnt about travel in Africa through mainly European accounts. European travellers in comparison have had more opportunities to shift opinions of Africa amongst the corpus, and subsequently, amongst the public too. A discrepancy therefore emerges when one considers that the opportunities for Africans to contest Eurocentric narratives within the corpus are minimal. Further, all seventy-nine volumes were mainly adapted from written European manuscripts and fifty-two of these volumes focused on accounts of imperialist or missionary enterprises. For instance, Europeans in West Africa, 1540-1560 (1942) is indicative of this trend because the publication recounted histories of Portuguese, Castilian, and British colonial trade and settlement using a collection of written documents.[11] Resultingly, differing source types, such as oral sources, are largely neglected. Publishing more ‘Travels of Africa’ is welcome, but the Society would do well to consider the histories and perspectives these sources do and don’t convey. Otherwise, maintaining current practices will perpetuate an imperially focused, and largely European, corpus.

The Society’s publication of Jacob Wainwright’s travel diary in 2007 marked an innovative step for the Society because it was the first publication that featured ‘a [B]lack African traveller who recorded an exploration’.[12] The once enslaved, then liberated and mission educated, traveller offered a unique travel entry which differed from earlier Main Series volumes on Africa, such as Duarte Barbosa’s Description of the Coast of East Africa (1866) or the journal of Vasco da Gama’s first voyage (1898).[13] Whilst Barbosa’s and Da Gama’s accounts maintained the Society’s commitment to publishing international travel, as these accounts were adapted from written European records they offered only a limited window onto the more complex narratives that could be told. In contrast, the adaptation of Wainwright’s personal written records, as well as a series of photographs and sketches taken by historical actors of differing ethnic and geographical origin to Wainwright, came together to create a more complex and accessible account of travel in East Africa and Britain.

Recent Main Series publications such as Pedro Paez’s History of Ethiopia (2011) and James A. Grant’s Nile Expedition (2018) represent more incremental changes in the publishing of accounts of travels in Africa.[14] Both volumes are based solely on European records, which limits the broader histories that these volumes could tell. The volume regarding Grant’s expedition (1860-1863) included 147 expedition sketches and photographs, which produced a visually complex representation of the Upper Niger Valley, but accorded little space to African agency. By comparing the adaptations of Wainwright’s, Paez’s, and Grant’s accounts, it can be suggested that whilst a European framework remains predominant within the corpus, the potential for including multiple source types and authors of differing geographical and ethnic origins has already been shown. Therefore, to mediate the power discrepancy already outlined, and which continues to be perpetuated in recent texts, a decolonial approach would require more African sources to be read alongside existing European ones.

Such an approach might be extended to the Society’s representative posts. Whilst member lists show that the Society’s public is international, and indeed global, a wider recognition of this fact might be achieved by the appointment of new International Representatives of the Society across the African continent. Currently, the Society has one representative for North Africa and none for any nation in Sub-Saharan Africa.[15] Promoting African academics to the position of international representatives could diversify the public by encouraging overseas subscribership, make African academics and archives more accessible due to proximity, and develop the decolonial aspect of the Society’s academic activities by sharing expertise.[16] For instance, academic staff of Cape Town University became international leaders, practitioners, and innovators of educational decolonisation during the height of the Rhodes Must Fall movement.[17] The promotion of African academics to the position of International Representatives of the Society can prove invaluable for the purposes of decolonisation by providing expertise in replacing colonial practices by postcolonial ones. As such, new international representatives could instigate critical debates regarding who the Society’s ‘public’ is and discern how best to choose, research, and edit rare accounts of travel.[18]

When viewing the Society’s existing list through a postcolonial lens, one can see that Main Series volumes on travel in Africa have predominantly featured imperial European authors to the exclusion of differing source types. Yet, by reflecting on the Main Series and the Society’s broader educational objective, it becomes clear that there is ample potential for, and indeed relatively minor obstacles to, implementing a decolonial approach.