by Nigel Statham

Volume 41 in the Hakluyt Society Third Series, An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, is the pioneering account of Tonga as told by William Mariner to by John Martin (1789-1869) who was a London-based, Edinburgh-educated medical man interested in anthropological subjects who wrote it down. This is his only book. He was inspired to write it by a chance encounter with its subject, William Mariner (1791-1853) who spent four years (1806-1810) in Tonga, in the South Pacific, one of the earliest European residents at a time before there was much European influence on the Tongan way of life.

New Edition: John Martin’s “An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands”

In 1963, when I was a nineteen-year-old undergraduate, I accompanied Danish archaeologist Dr Jens Poulsen to Tonga. Dr Poulsen was the first archaeologist to use modern archaeological excavation methods to investigate Tongan antiquity. Tonga was well off the beaten track in those days, still sometimes referred to by Captain James Cook’s name for the archipelago, the Friendly Islands. There was still no regular aerial transport, and most visitors travelled on cargo ships.

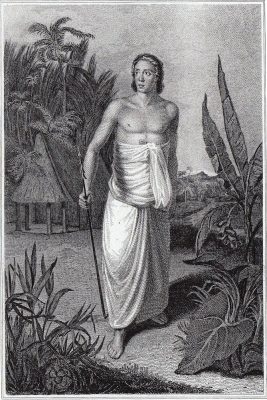

When I returned to Australia, my father marked the occasion with the gift of a book, John Martin’s Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands …from the extensive communications of Mr William Mariner, several years resident in those islands… Two things immediately struck me about this work: first, the informant, Mariner, was just nineteen when he left Tonga, the same age as I was. Inevitably I compared his experience with mine, and wondered whether I could have conducted myself with such maturity, courage and percipience as he. Young Mariner had joined the privateer-cum-whaler, Port au Prince, at the age of 13 in 1804 as the captain’s clerk. Two years into the voyage, the ship called at the seldom visited Tonga Islands, where the crew was mostly massacred by the Tongans, and the ship burnt. Mariner, having been spared the massacre, was adopted by the paramount chief, and for the next four years lived the privileged life of a Tongan chief, participating fully in its ceremonies, daily routines, and wars. Apparently determined to make the best of what could not be helped, Mariner became steeped in all aspects of the culture, and when he got away at the end of 1809, he was a confident aristocrat, with a native command of the language, and as history was to prove, possessed of a most remarkably retentive memory and acute insight.

Second, I could immediately see that Mariner’s Tonga of 150 years previously was very much recognisable as the Tonga that I had seen during my two months archaeological experience. Tongan had changed much less in those 150 years than it has in the subsequent 60. Tonga in the early 1960s was still very traditional: the overwhelming majority of people lived a traditional life of subsistence agriculture in their villages, very few had travelled overseas, and most of those had been to study, usually medicine. There were almost no private motor cars, bicycles being the common form of wheeled transport but in the gardens and for carrying produce to market, the two-wheeled, horse drawn dray was ubiquitous. For most people their cotton clothing and steel tools, the sugar and flour in their diet and their ardent Christianity, were what chiefly distinguished them from their ancestors. It was obvious to me that Mariner’s account was as much a window into the Tongan present as it was into the Tongan past, so much so that when social anthropologists began taking an interest in Tonga, Mariner was the primary source to which they turned, and against which they measured social change.

Not the least remarkable aspect of the work, and of particular interest to me as a student of linguistics, was the appendix on the Tongan language – grammar, syntax and vocabulary. This was the first systematic, published attempt to describe any Polynesian language. Missionaries at that time had studied Tahitian, and others were making a start on New Zealand Maori, but none of them at that time had the intimate linguistic knowledge that Mariner did, nor apparently, did they have the sophisticated assistance of a scholar to match Mariner’s ghost writer, John Martin. The first meeting between Martin and Mariner in 1811 shortly after the latter’s return to London was a matter of pure chance, but conversation soon revealed to Martin that Mariner was a uniquely rich informant. Martin himself, newly graduated in medicine from the University of Edinburgh was in his own way as precocious and inquisitive as Mariner, well-versed in contemporary philosophical currents and intrigued by the question of human nature: whether it was innate or culturally determined. A case study of a society scarcely touched and not influenced by European society, was a unique research opportunity. The collaboration of these two young men of extraordinary talents, well matched in their intellectual vigour and pertinacity, resulted in a work which can properly be called a pioneering study of social anthropology, well ahead of its time.

Martin assembled the cultural and social information systematically in thematic chapters, but a considerable body of information is given in more concrete form, in the first half of the work in the form of a narrative of Mariner’s experiences. His sojourn coincided with a watershed period in Tongan political history. The traditional hierarchy of chiefs in this very formal, orderly society had collapsed under the assault of contested titular successions, assassination and civil war in which Mariner’s patron, the chief Fīnau, was a leading participant. Mariner not only had a grand-stand seat in the later events, but was an active (if subordinate) participant. Accordingly, Mariner was witness to martial brutality, savage and gratuitous cruelty, murder, and political intrigue and deceit. The information recorded would be otherwise unavailable given the partiality of oral tradition.

It would be remarkable if Mariner did not suffer post-traumatic stress disorder, but if he did there is no trace of it in the bare facts of his later years. Little is known of his life after Tonga: he married early, fathered 11 children with his wife, had a conventional though prosperous career in commerce and finance, and unhappily was implicated in a financial scandal known as the Exchequer Bills Forgery. He died at the early age of 64 apparently by accidentally drowning in an urban canal. Much of what is known of his post-Tongan life is due to the indefatigable research of a great, great grandson whose abiding interest was his ancestor’s remarkable history.

If there is little trace in Mariner’s later life of his Tongan experience, the same cannot be said for me: Mariner made such an impression on me that after I graduated in linguistics, I became a specialist in Oceanic and especially Polynesian languages. Like Mariner, I acquired native fluency in Tongan, translated many works into and out of that language, and worked on the first monolingual Tongan dictionary. My career can be said to have come full circle when I was invited to edit a new and critical edition of An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands. Mariner unwittingly started something that has not concluded.

I am indebted to my co-editor Ian Campbell for his enormous contribution to the volume, and especially to the Introduction to the background and history of the islands. He writes that his trajectory was somewhat different from mine. He first heard of Mariner and the Port au Prince massacre at the age of eight, and remembers playing boyish games with one of the carronades from the ill-fated ship. When he was eleven he read a novel set in North America about an English boy who was adopted into an American tribe for a time, so with an early interest in misplaced individuals in communities not their own, there is a retrospective inevitability that sooner or later he would come across Mariner again. So in a way, working on a scholarly edition of Mariner was a climax, though a belated one, to a career as a historian of the Pacific islands, and the closing of a circle.