by Captain Michael Barritt RN, Past President of the Hakluyt Society

‘Your friend Capt. Johnstone is or will be confirmed.’ The First Sea Lord, Earl St Vincent, lost no time in assuring his correspondent, the eminent and influential Sir Joseph Banks. James Johnstone, recently returned from successful command of a sloop in the West Indies, was just one of the veterans of the eighteenth century Pacific voyages whose front-line employment on survey work in the wars of 1793-1815 would be urged by Banks. The mapping and charting campaigns on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America, and the exploratory voyages into the surrounding oceans, were a school for men who equipped the Royal Navy with superior navigational intelligence that played a significant part in the defeat of the Napoleonic empire. The most skilled of these men would form the cadre which made new surveys world-wide in the nineteenth century, establishing the fame of the British Admiralty chart. Their war-time endeavours are described in Nelson’s Pathfinders: A Forgotten Story in the Triumph of British Sea Power to be published in July 2024 (https://yalebooks.co.uk/book/9780300273762/nelsons-pathfinders/).

>Murray had been interviewed and recommended for the work by William Bligh, who was standing in for Dalrymple during an indisposition. Bligh himself, together with William Broughton, another distinguished Pacific voyager, had been deployed by the Admiralty to improve the navigational information for the ships blockading the Scheldt estuary. Bligh’s work is commemorated in the name of one of the hazardous banks in the approaches. This intricate and challenging theatre of operations saw the involvement of one of Vancouver’s midshipmen when a major operation was undertaken in 1809 to neutralise the deep water base at Flushing. John Sykes, now a post captain in command of the 50-gun ship Adamant, made a sketch survey of a buoyed channel along which troops were transported to complete the encirclement of Walcheren. In the same year, Joseph Baker, who had compiled the fair sheets from Vancouver’s voyage, rendered a sketch of the banks of the southern part of the Baltic Sea in which he was operating in the frigate Tartar. Possibly Vancouver’s best known lieutenant, Peter Puget, had taken part in combined operations in inshore waters at Brest, Copenhagen, and Walcheren. In his final appointment as Commissioner of the Navy at Madras, he developed a new yard at Trincomalee, where he made a fine survey.

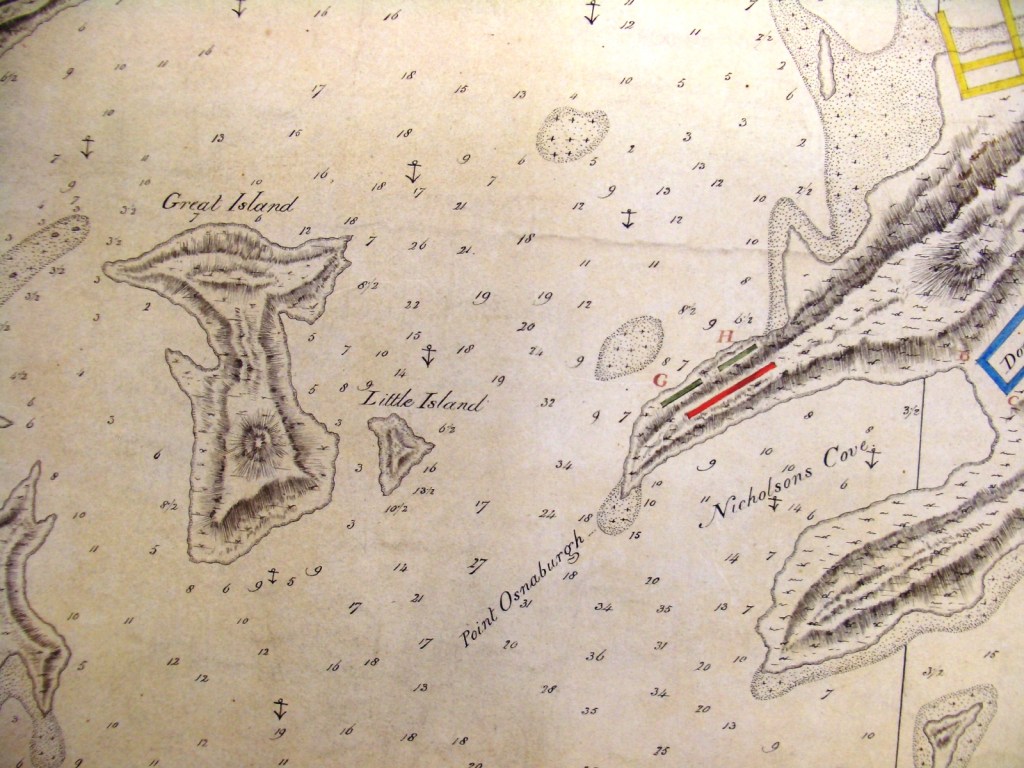

Detail from Peter Puget’s survey of Trincomalee.

Men who had served with Bligh in the Pacific had meanwhile contributed surveys from that same theatre. Thomas Hayward, who had survived a second open boat voyage after the shipwreck of Pandora on her homeward voyage with captured mutineers from Bounty, redeployed to Eastern Seas on the outbreak of war. He soon earned the patronage of Peter Rainier, an admiral with an appreciation of the importance of hydrographic intelligence. Not long after completing a survey during the operation to capture Trincomalee, Hayward was given command of the ship-sloop Swift and tasked with patrols and surveys in the Eastern Archipelago. His work was cut short when Swift went missing in a typhoon. He was survived by another of Bligh’s midshipmen, Peter Heywood. Influential connections had earned him a pardon after conviction for mutiny, and continued to secure him steady advancement. He also earned Rainier’s patronage, justified by a succession of fine surveys during commands in the East Indies. He was marked out as an expert practitioner by the time of a deployment to the River Plate in 1809 in which he coordinated surveys to path-find for the British squadron.

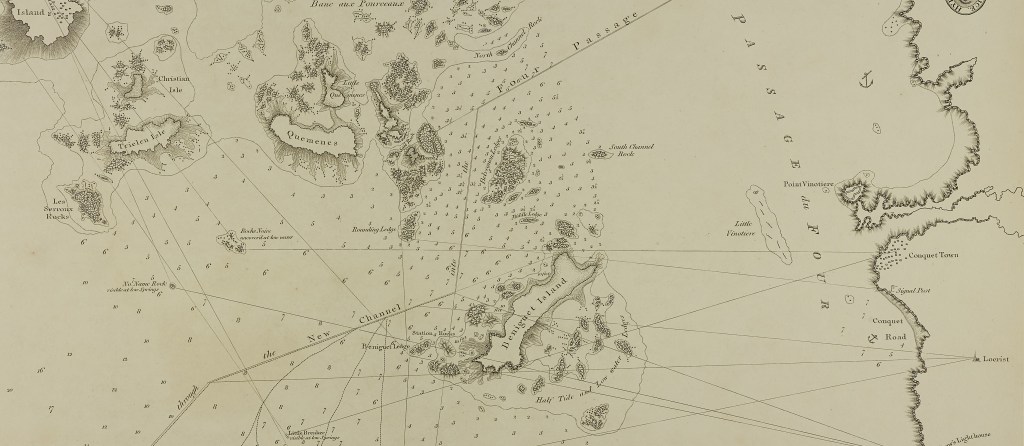

Back in the European theatre two men who made most significant wartime contributions had honed their skills in working with the military surveyors on the Atlantic coast of North America after the Seven Years War. John Knight went on to be a prolific contributor of information for charts used by the fleet. Amongst his most important products were small-scale passage planning charts for the Mediterranean, and a set of plans of the intricate approaches to the Brest base of the French Atlantic fleet replete with operational information such as the range of shore batteries. He was followed here on the enemy’s doorstep by Thomas Hurd, applying the same rigour as in the Gulf of Maine and the Bermuda archipelago.

Detail from Thomas Hurd’s survey in the approaches to Brest.

It was that experience which inspired Hurd to advocate successfully for a permanent establishment, the foundation of the Royal Naval Surveying Service. He would be assisted by Peter Heywood. He would be succeeded by Edward Parry, famed for his part in the Arctic element of the post-war resurgence of exploration. He in turn was succeeded by Francis Beaufort, who had earned the championship of both Dalrymple and Heywood for wartime surveys in the Indian Ocean and Plate Estuary. During the war with Russia in mid-century Beaufort would urge his experienced surveyors in the Baltic and Black Sea theatres to be ‘the Admiral’s eyes’ a crucial role that has continued into the twenty-first century. Alongside this, the hydrographic specialists of the Royal Navy would continue to provide records of exploration and encounter that shine out in the editions of the Hakluyt Society.